Arthur Ransome - Author

'Houses are but badly built boats so firmly aground you cannot think of moving them. They are definitely inferior things, belonging to the vegetable not the animal world, rooted and stationery, incapable of gay transitions'.

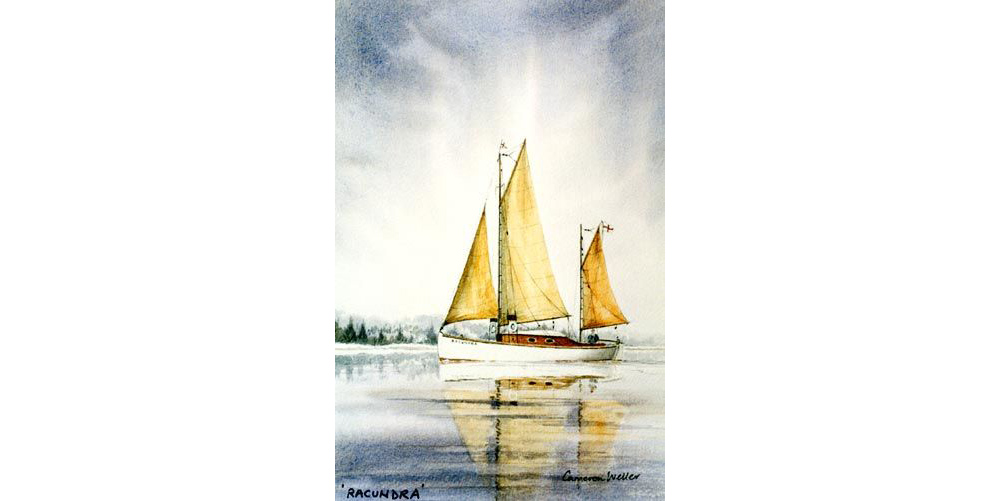

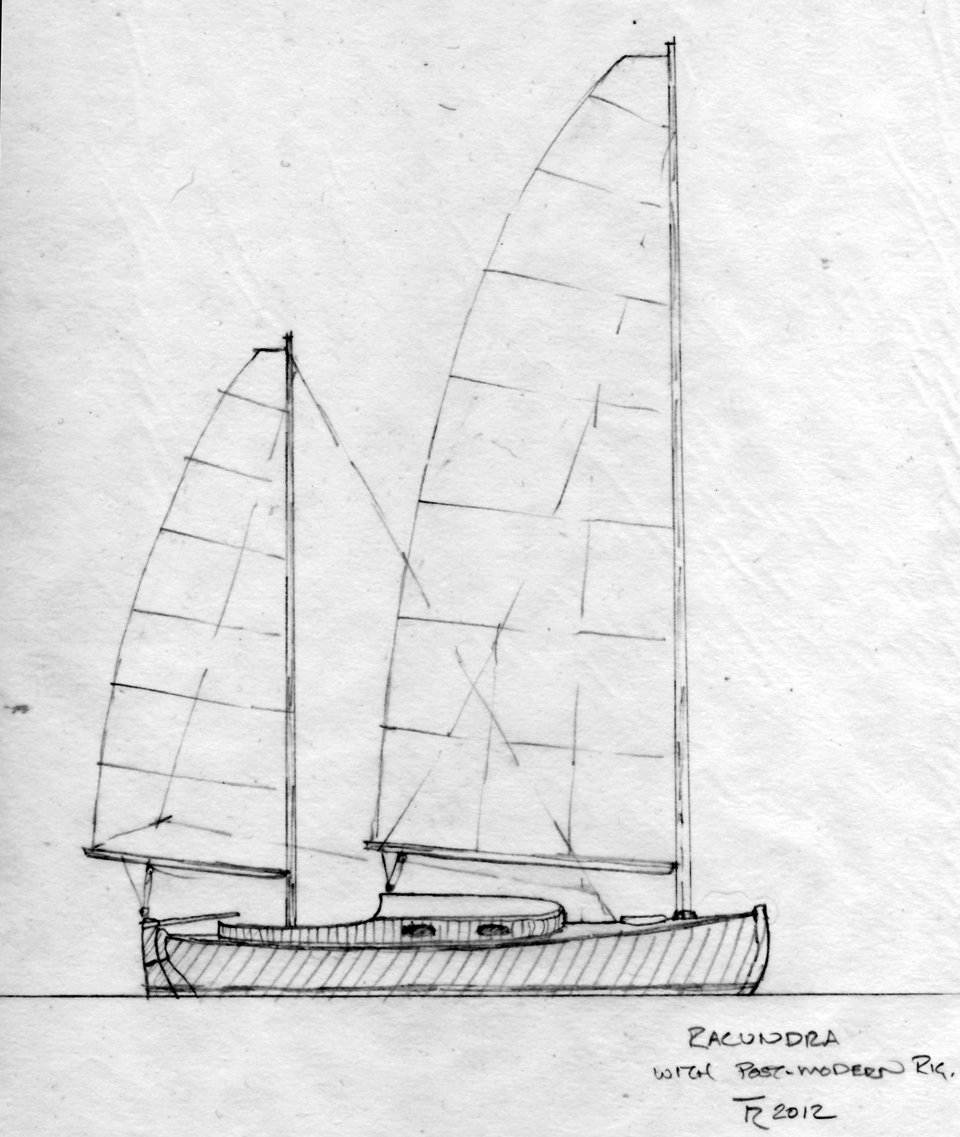

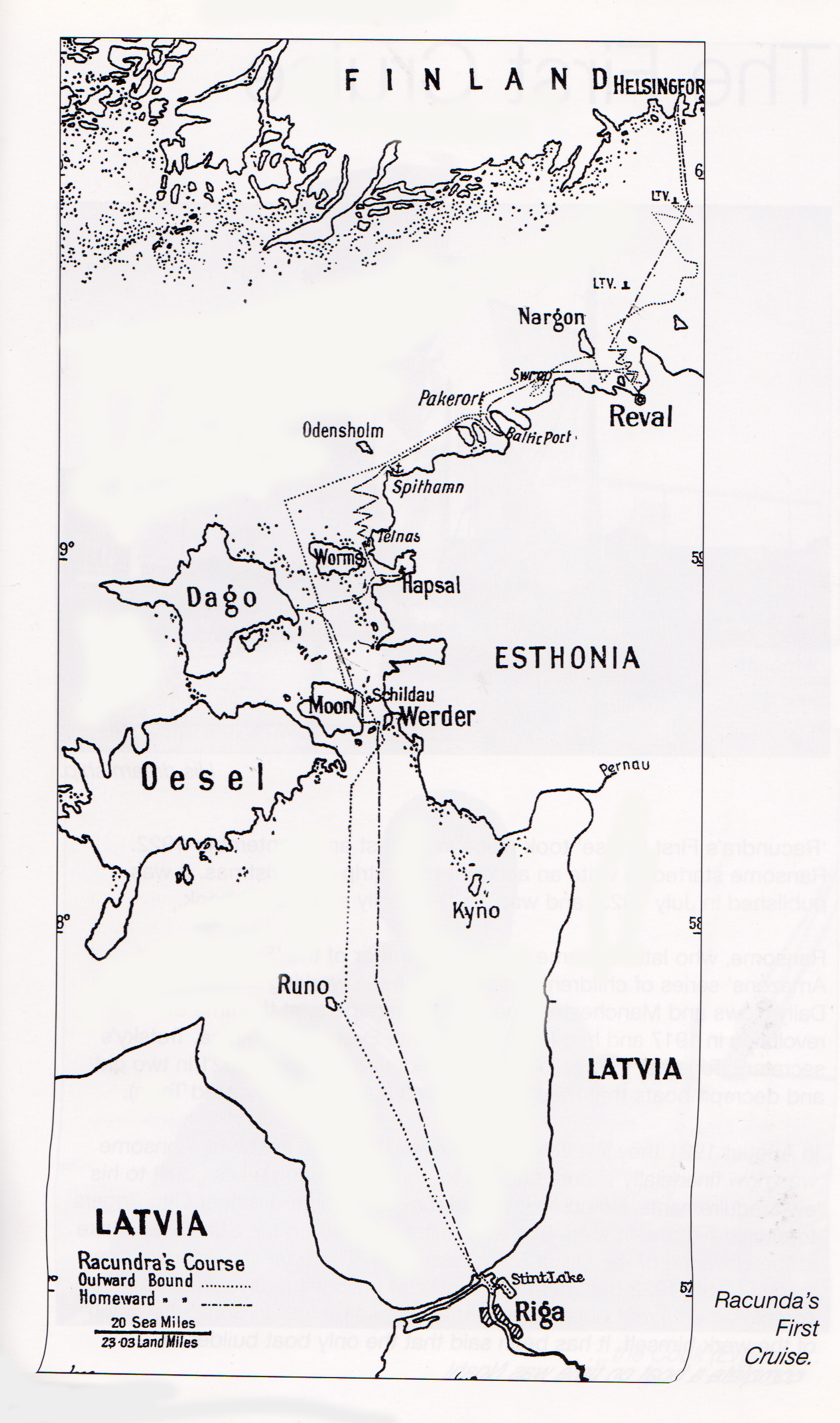

Racundra's First Cruise.

In this book (which is unsurprisingly about Racundra's first cruise), he writes an essay of the theft of his sails from his first boat nicely called 'Slug'.

There are degrees in robbery. Some thefts are worse than others. I am prepared to forgive natural thefts such as cherry-stealing, in which boys are no worse than chaffinches, and, however they may hurt the pocket, do not grievously offend the moral sense. The theft of money is more sordid, contaminated as it is by the 1east uplifting of human interests, but it has a practical, sensible character, and can often be justified. It is an evil involved in an imperfect system of distribution. The theft of a fountain pen comes nearer sin. It can never be to the thief the intimate thing that it was to its owner. The gain of the thief is less than the loss occasioned to the owner. The theft of clothes may or may not belong to some category. The theft of new clothes, if they fit the thief, I find easily forgiveable, at any rate more easily forgiveable than, for example, the abduction of a worn old shooting coat in which every rent and patch is as it were a notch on the tally stick like an entry in the diary of the owner's life. Horas non numero nisi serenas, (I don't count the hours unless they're tranquil) is as true of the patches in a shooting coat as of the moving shadow of the sundial. Similarly, I find the theft of a fishing rod far worse than the appropriation of any quantity of mere hooks and similar tackle. The quality of book stealing depends entirely on the personal characters of the thief and the sufferer. I have myself on one on two occasions stolen books, committing crimes for which if there is to be a summing up and general judgment day I confidently hope to be forgiven. And once at least in stealing a book from a man who never read it but owned it merely as a sort of filthy ostentation, I performed an act for which, if there is justice in heaven, I expect not forgiveness but reward.

But if the theft of a book may be an act of virtue there are other thefts as black as murder, no; blacker, like the theft of a man's soul. The theft of a cripple's wooden leg is a deed whose ugliness will be pretty generally admitted, since, reducing him to immobility, inflicting on him paralysis, it is a particularly vile kind of assault. But even that ls not so vile a crime as that which is still ruining the world for me, stopping the cruise of the Slug almost in its auspicious outset. Next to the theft of a man’s soul, I can think of no villainy so utterly abominable as the stealing of the mainsail of a little ship. And that unthinkable as it must be to any honest man, loathsome to any sailor, actually occurred, on the night between July 7 and 8, in Laheps Bay in Estonia.

Now the mainsail of a little ship is her very soul. Take it away, and you take away the thing that distinguishes her from mere water carriages propelled by oars or steam or petrol. Removing it, you remove the thing that links her with the wind, with the seagulls she resembles. You commit worse than murder. You take the very soul out of her and leave her a dead thing.

It was not a new sail. We had spent the whole of July 6 in patching it with bits of tablecloth. Five laborious patches we had put it. Nor was it a good sail, but made of some inexpensive material, intended, I believe for the underclothing of the Russian army. But patched and cheap as it was, it was wing enough to lift her through the blue waters of the Baltic Sea, and indeed, like a great wing, towered proudly above her stumpy mast, curving away wing-like to the end of her long boom.

I had left her, with her foresail neatly gathered about her bowsprit, and the great mainsail wrapped about boom and gaff, and laced with the main-sheet, as neat as a fop's umbrella in repose. She rode to a buoy, improvised during the morning. I had sunk a sugar case with wire rings at the top corners, from which wires meeting in the middle were fastened to a twisted wire rope. With terrific labour, sweating in the sun, I had dragged heavy stones out to sea. Struggling under water, I had done diver's work, and planted them one by one in the sugar case. To the end of the wire rope I had fastened a little barrel. I had taken her a little trip to try certain small Improvements In rigging, and we had returned, tied up to our own buoy, in itself a satisfaction, and swam ashore, stopping again and again, as we walked from the beach, for the pleasure of seeing her there swinging so pretty, with her head under her wing, like a seagull resting for the night, with the blue bay opening out behind her, and the sun setting away in the north behind the Baltic Sea.

And then, in the morning, I had stayed at home and worked, my mind, none the less, caressing her. Women came up from the shore, and told me, in answer to my questions, that she lay there all right. At last, after luncheon, I took the tiller on my shoulder and set out for the shore. To get to the shore, you have to cross a wide strip of sand with glaucous coloured sharp edged and sharp pointed grass, and, at the very edge of the sea there is a raised bank, so that the little ship is not visible until you are actually within a few feet of the water. The moment I stood on the bank, I knew that something was wrong. The boom was lying flat, not cocked up perkily as I had left 1t. I thought that boys had been on board and meddling with the ropes. When I caught the sunlight on the boom, and saw instead of sail, bare wood, I could not believe it. We swam off. The wind was from the land, and the water had turned very cold in the night, but not so cold as our hopes, which, until that moment had been at boiling point, thinking that next day we should continue our cruise, and round the Pakerort lighthouse, and away by Baltic Port and Odensholm, for Hapsal and the Island of Dago.

We clambered on board, to the last-minute thinking that perhaps some imp of mischief had taken off the sail and stowed it in the forecastle. To the last minute I could not believe that any man could be so vile. But, as I tumbled in over the stern, my hopes and my faith in humanity fell together like plummets, and I knew the worst. The boat was strewn with little scraps of rope, clean cut with a knife. The thief had simply cut all at impeded him, and left the boom, bare, stripped among the wreckage.

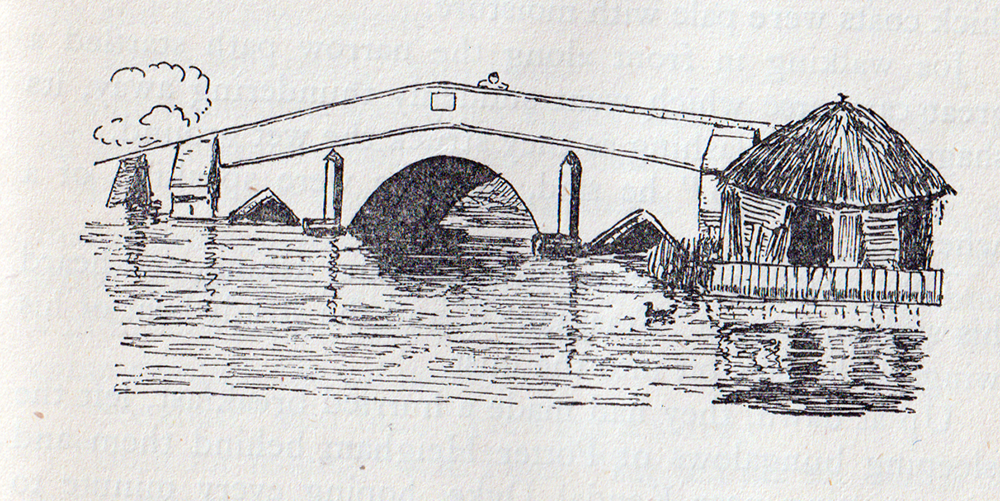

The Big Six

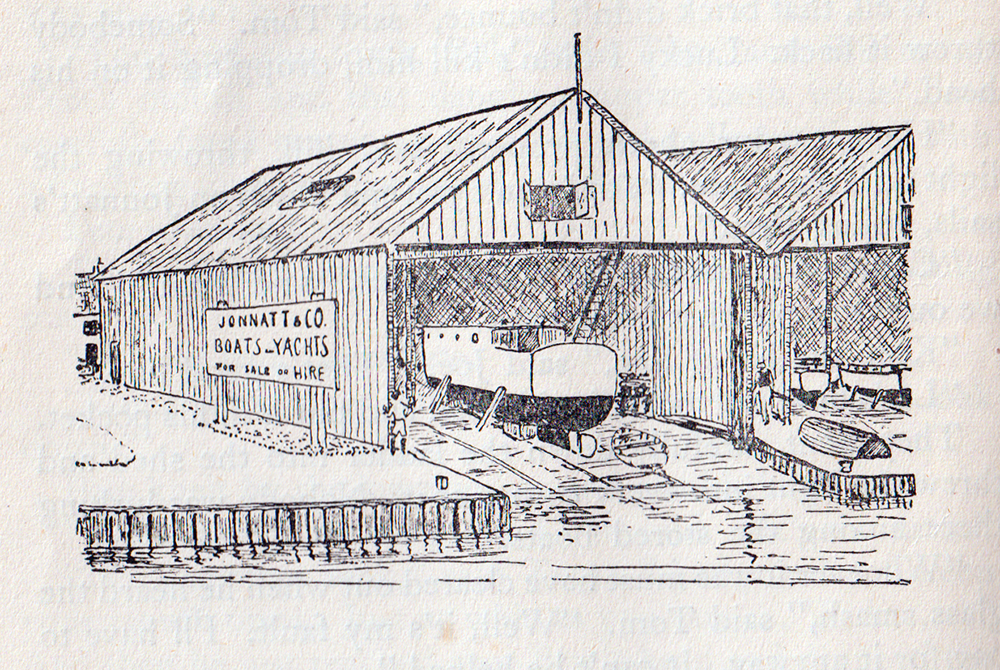

'The Big Six' a children’s detective story is great for 'spotting' places on the Broads. The bridge picture for example, is an easy one!

Swallows and Amazons

Coniston Water clearly is the setting of Swallows and Amazons, a children's adventure novel, first published on 21 July 1930 by Jonathan Cape.

‘All the places in the books are to be found, but not arranged quite as the ordnance maps’, Ransome assured his readers.

Nevertheless, Coniston Old Man features as one generation’s Matterhorn, and the next’s Kanchenjunga; and Peel Island’s secret harbour is borrowed from Wild Cat Island.