Day 1 - Edinburgh / Union Canal / The Lang Whang / New Lanark

page 2

Our target for the first day's ride was only 30 miles away at New Lanark Youth Hostel, luckily, we had anticipated a late, leisurely start. Three of us eventually pedalled off westward - two heavily overloaded and unsteady, the third my sister, a keen hillwalker and cyclist, who was to lead us through Edinburgh’s urban sprawl. My family often warns that hiking with her means your feet must bleed before it counts as a proper walk. Today, the risk we faced was falling behind, and then feeling inadequate and discouraged before even 10 miles had passed. Fortunately, the Union Canal route proved enjoyable; as part of a national cycle path to Glasgow, its narrow towpath and a few dog walkers slowed her pace enough to let Chris and me appear “cycle fit,” and able to keep up. Initially, the path followed the ‘Water of Leith’, Edinburgh’s ‘hidden river’, which runs through the city centre but remains a sanctuary for wildlife and mature trees, largely concealed below street level.

I left my hometown of Edinburgh 40 years ago, and like most waterside areas in large towns, it has undergone extensive development. The village of Balerno, which in my youth was significantly out in the countryside, is now well within the city's suburbs. Here, we left the cycle path and civilisation and gingerly took the A70.

At this point, we were seen off and left to our own devices. I took the lead, climbing a steep hill and around several bends.

After about the first mile on our own on our proposed 500-mile journey, I turned around to find Chris missing—he had vanished!

What would his wife say?

I stopped at a field entrance and waited.

About 15 minutes later, he appeared over the hill, a sight I would become accustomed to over the next 16 days.

Wearing the Green Jersey

The delay was because Chris finally decided to shed one of his two fleeces, despite earlier repacking efforts. He spent time rummaging through his panniers to hand one fleece to my sister to take back to base camp. Had he thought of this in the morning, he might have avoided hours spent in Tiso’s searching through the bargain bin for the right fleece. His purchase unsettled me; I was already wearing the same fleece from the same store.

Throughout our journey passers-by must have thought they were seeing double—we had identical outfits, we even had bikes of the same make and colour. We would have put a sponsored team in the Tour de France to shame. The fleeces were excellent choices though: indispensable for Scottish summers, useful for warmth and repelling midges, and perfect as pillows.

Don't Whang about on the Lang!

The A70 road here is locally known as the ‘Lang Whang’. A ‘whang’ in Scots tongue refers to a long strip of leather and aptly describes the road that crosses high, desolate moorland, climbing several times above 1,000 feet. In winter, the road is often closed, even with modest snowfall. The ‘Lang’ bit of the ‘Lang Whang’ lived up to its reputation—seemingly endless, despite sweeping views over the Forth and Pentland Hills but for us thankfully a pleasant ride

Civilisation quickly faded from view, yet the ride wasn’t as hard as expected, aided by a dull, windless day. We passed through the small towns of Carnwath and Carstairs. Neither of which has any redeeming features.

New for Old

Late in the evening, we finally spotted signs for New Lanark Youth Hostel, having passed through Lanark itself. For context, New Lanark was founded in 1786 and is probably older than Lanark (the town).

I thoroughly enjoyed the day’s ride, although the steepness into the deep dark, Clyde gorge I was now at the bottom off worried me. Getting back out again in the morning was going to be a wee bit of a struggle for us ‘newbies’ not yet honed into cycling fitness. The challenge tomorrow was to get to Ardrossan, which was 53 miles away, and to catch the 3 pm ferry to Arran.

The Great Fall at the Clyde

Arriving at the hostel alone, I realised Chris was still somewhere behind, likely at the top of the hill. Eventually, he showed up, explaining that he’d walked his bike down the steepest sections because he wasn’t comfortable riding downhill. We planned a quick ride around the area, hoping to find a shop for something to make for dinner. Just as I was about to mount, I heard a loud crash. Turning around, I saw Chris on the ground—he’d fallen, unable to get his feet into the toe clips in time. Of all places for this to happen, it was in the centre of the busy and picturesque World Heritage Site of New Lanark. Tourists quickly pieced together the scene: a bike at the bottom of a steep hill, an injured cyclist. Oh! Dear! They concluded that Chris must have experienced catastrophic brake failure and had heroically stopped himself using his knees as brakes. A crowd of concerned international visitors rushed to his aid, their compassion almost overwhelming.

I then left Chris settled against a wall, sipping water (but not before snapping a photo of his scrapes). Thankfully, his injuries amounted to nothing more than a grazed knee, but the commotion he caused was impressive. When I returned, Chris was already entertaining a group of women, recounting our journey from Edinburgh and his cycling exploits. It became apparent that Chris had a talent for attracting the admiration of ladies of the same age, and over the coming weeks he was often seen sharing tales with groups of white cardiganed, grey-haired ladies. Eventually, I managed to coax him away and we retreated into the New Lanark Youth Hostel.

The Couscous Mountain

My attempt to find a food shop ended in disappointment—the nearest one, was back up that relentless, switch-backed hill. The thought of climbing it again, especially on an empty stomach, meant it was not going to happen.

Managing daily rations becomes a true challenge for any cyclist who must travel light. Although I carried an emergency dry food pack, opening it on the very first night didn’t feel right. Instead, we were left to choose from the questionable assortment of pot noodles and tinned foods sold at the hostel. We settled on dried spicy couscous, intriguingly packaged in East Grinstead—a place I never associated with any sort of culinary excellence, let alone couscous. After tasting it, I remained convinced that East Grinstead had little claim to such a title. The packaging promised the meal was fit for two, a claim we didn’t believe, so we bought two packets. In reality, just one packet could probably have fed the entire population of New Lanark.

An Evening Walk

The hostel itself was excellent: modern, with en-suite rooms accommodating no more than four people in each room. After preparing our much-deserved meal, I took a short walk along the Falls of the Clyde. Even in mid-summer, the falls were in full flow—a truly impressive sight. If I’d had more time, perhaps I would have been inspired to write a song about it.

I'll sing of a river I'm happy beside

The song that I sing is a song of the Clyde

Of all Scottish rivers it’s dearest to me

It flows from Leadhills all the way to the sea

It borders the orchards of Lanark so fair

Meanders through meadows with sheep grazing there

But from Glasgow to Greenock, in towns on each side

The hammers' "ding-dong" is the song of the Clyde

Kenneth McKellar

Chris, unfortunately, spent most of the evening repacking his panniers after realising the first law of cycle touring: whatever you need will always be in the other pannier, but you only discover this after emptying the first one entirely. This was particularly evident with his elusive cutlery, which is why Chris at future meals could often be found eating yogurt and the like, with a large plastic ladle.

Late Night Arrivals

I’d been here before, and even under a grey evening sky, the scenery remained stunning. After a stroll, I went straight to bed, already anxious about the climb that awaited us and the 53 miles we had to cover by 3 pm the next day. By this time, Chris had managed to scatter all his belongings around the room, making our four-bed dormitory look as though it was occupied by four people instead of two. Lying in my bed, I remarked that it seemed we’d have the place to ourselves – when, as if on cue, the door rattled and two large, bikers entered.

These weren’t the Lycra-clad, peace-loving cyclists, but the other kind. Being organised, I’d packed my gear in advance, so my things were neatly in my corner. Chris, however, had abandoned his system of meticulous lists and bag labelling, and chaos had taken over. Having never stayed in a hostel before, he found himself thrown in at the deep end with our new roommates. He attempted to tidy his things into several black plastic bags, which only made matters worse. The reason for the bags was that, his panniers, unbelievably, weren’t waterproof!

Lost in Translation

To gather his belongings, he swept around the room piling everything on his bed, creating a small mountain of 'stuff'. Apologising repeatedly to the larger of our two guests. I decided it best to feign sleep, occasionally feigning a snore, hoping it would prompt everyone to be quiet.

We soon learned that our ‘Hells Angels’ were actually a father and son from Holland, wrapping up a two-week motorbike tour of the Highlands. As is typical, their English was excellent, spoken with a gentle Dutch accent. Chris, being slightly hard of hearing and probably nervous, however, often responded to questions with unrelated answers. Topics like couscous and East Grinstead surfaced in conversation, and confusion reigned for a while.

Eventually, things quieted down, but I barely slept, my mind churning with thoughts about the long climb ahead, the prospect of a breakfast of water-only porridge, and the race to reach the Arran ferry by 3pm.

The Union Canal - taking us out of the city.

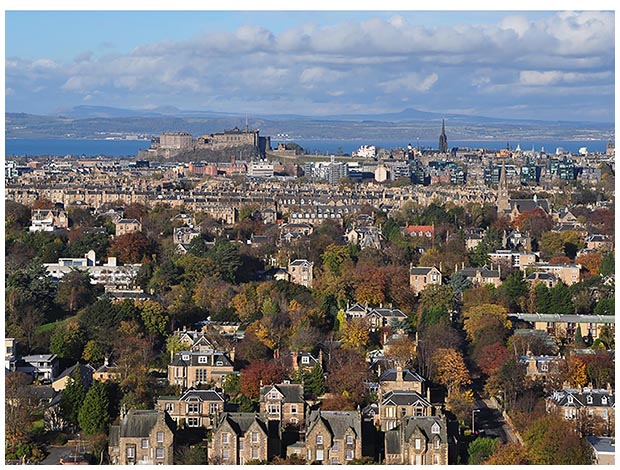

Auld Reekie - on a rare clear day

Its long, its bleak, its the Lang Whang

New Lanark features on some very strange looking banknotes.

New Lanark and the River Clyde.

A History Lesson

The cotton mills and village of New Lanark in South Lanarkshire sits in a deep, leafy glen beside the upper reaches of the Clyde River. There is nothing quaint or pretty about the elongated stolid stone buildings, but you are struck by their neatness and the way they blend in with the surroundings. The whole town was one giant factory and housed the workers at the mill. If the living conditions seem cramped and unhygienic to visitors today, it must be remembered that, when built in 1785, it was a model village, offering far better conditions than mill workers could expect anywhere else in Britain.

Built by the leading industrialist David Dale, it eventually became the property of his young son-in-law, Robert Owen. Owen was a social reformer who wanted to prove to the world that it was possible to make a good profit from industry without subjecting the workers to miserable, underpaid, unhealthy conditions. Over time, he increased wages, demanded that children under 10 go to school instead of to work, organised medical services, a nursery, and adult education, as well as ensuring a good, healthy standard of living. Owen believed that harsh conditions in factories were damaging to people. He felt that machines should serve the people, rather than the other way around.

The mill prospered, the workers were happy and had enormous love and respect for their boss, and the world took notice.Nevertheless, Owen was not popular with other manufacturers who saw no value in abolishing child labour or shortening working hours.

If there is one thing we should all remember Owen for, is his insistence that all schools have playgrounds, previously to this ‘invention’ they did not exist at all.