Belguim/France

WW1 Battlefields

A week's tour cycling around the WW1 Western Front. Day tour of the Somme following the fate of the RNVR. Daily trips staying in the town of Ypres. Highly recommended areas for this sort of touring, lots of places to visit and the Belgians definitely have better roads for cyclists than Britain.

March 26, 2015A DAY TOUR AT THE SOMME (about 2 hours away by car from Ypres)

Our day at the Somme was to study the fate of the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve. They were 'conscripted' by the army and badly used in this first battle. The Army High Command saw them as 'undisciplined', coming from the Navy they were allowed to have beards and wear Naval insignia on their army uniform. One might say "not in good form, old chap".

We picked on this regiment and tried to follow what happened on the day of the charge and its aftermath.

A short history. (RNVR) was formed in 1903 by the Naval Forces Act 1903. When WW1 broke out, the RN had sufficient manpower to cope with its maritime tasks, & therefore with the exception of a few RNVR trained signalmen & wireless telegraphers, it did not need the majority of the keen volunteers who were anxious to put their training to practical use. However, though the Navy did not want them, the Army did. On 4th August, 1914, men of the RNVR found themselves formed into the Royal Naval Division (RND) for military service on land.

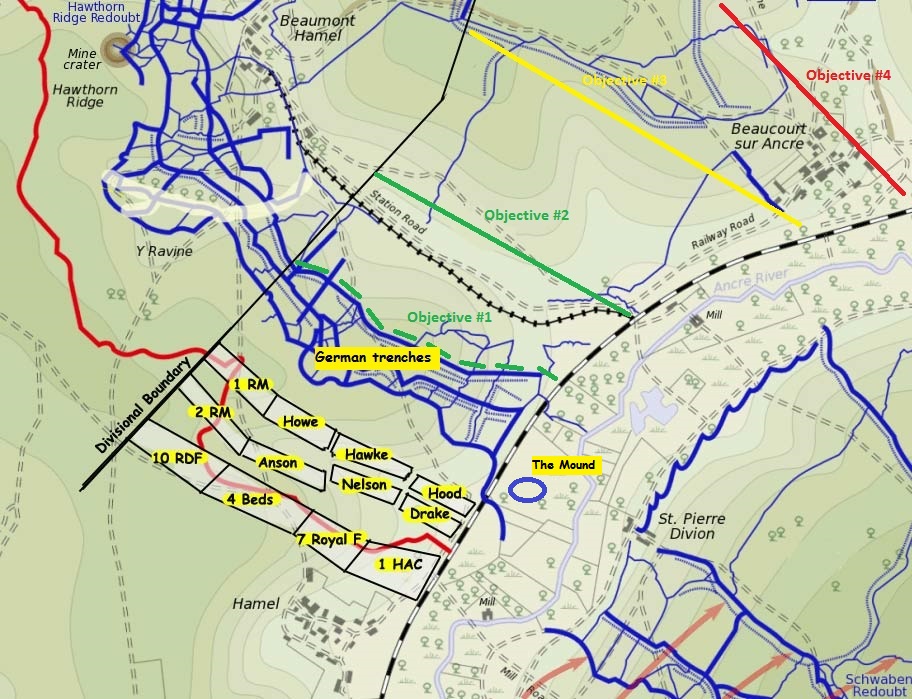

After the evacuation of Gallipoli, the RND moved to France where it participated in the final phase of the Battle of the Somme, advancing along the River Ancre to capture Beaucourt. The division had four objectives during the Battle of Ancre, the Dotted Green Line, the German front trench, then the Green Line, the road to Beaucourt station. The road ran along a fortified ridge. The Yellow Line was a trench which lay beyond the road, around the remains of Beaucourt on its south-west edge and the final objective, the Red Line, was beyond Beaucourt, where the division was to consolidate.

The plan was for the battalions to leap-frog towards the final objective. The 1st RMLI, Howe, Hawke and Hood battalions were assigned the Dotted Green Line and the Yellow Line, the 2nd RMLI, Anson, Nelson and Drake battalions were to take the Green and Red lines. When the battle began in the early hours of 13 November, platoons from the 1st RMLI crawled across no-man's land towards the German line. A creeping barrage was fired by the British artillery but many casualties were suffered in no-man's land, about 50 percent of the total casualties occurring before the first German trench had been captured. German artillery-fire and machine-gun fire was so effective that all company commanding officers of the 1st RMLI were killed before reaching the first objective

The German trenches had been severely damaged by the British bombardment, the attackers lost direction and leap-frogging broke down. Lieutenant-Colonel Bernard Freyberg did not wait for the Drake Battalion as planned. After leading the Hood Battalion to the Green Line, he pressed forward with the remaining men of the Drake Battalion. The station road served as a useful landmark and allowed the attackers to orient themselves and re-organise the attack. The next bombardment began on time at 7:30 a.m., allowing the British to advance towards the Yellow Line at Beaucourt Station.The Nelson, Hawke and Howe battalions had suffered many casualties, including two of three commanding officers; Lieutenant-Colonel Burge of the Nelson Battalion was killed whilst attacking a fortified section of the Dotted Green Line and Lieutenant-Colonel Wilson was severely wounded attacking the same objective. Lieutenant-Colonel Saunders was killed early in the battle but the Anson Battalion still managed to capture the Green Line and then advanced to the Yellow Line, after making contact with the 51st Highland Division to its left. By 22:30 hours, Beaucourt had officially been captured.

On 17 October, just before the Battle of the Ancre, Paris was wounded and replaced by Major-General Cameron Shute. Shute was appalled by the un-military "nautical" traditions of the division and made numerous unpopular attempts to stamp out negligent hygiene practices and failures to ensure that weapons were kept clean. Following a particularly critical inspection of the trenches, Sub-Lieutenant A. P. Herbert (later a humorous writer, legal satirist and Member of Parliament), wrote:

"... that shit Shute."

The General inspecting the trenchesExclaimed with a horrified shout

"I refuse to command a division

Which leaves its excreta about".

But nobody took any notice

No one was prepared to refute,

That the presence of shit was congenial

Compared to the presence of Shute.

And certain responsible critics

Made haste to reply to his words

Observing that his staff advisors

Consisted entirely of turds.

For shit may be shot at odd corners

And paper supplied there to suit,

But a shit would be shot without mourners

If somebody shot that shit Shute.

The Somme -Route One

Make your way, via various motorways past the city of Arras. Leave the motorway at the BAPAUME junction. Wind your way through Bapaume turning left onto the D929 ALBERT road. ¾ of the way to ALBERT, drive slowly through the scruffy village of POZIERES, and in the middle of the village, turn right onto the D73 to THIEPVAL. At the T junction in Thiepval, turn left to the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme (those who have no known grave) and the visitors’ car park. (The visitors centre has numerous books and good loos.)

Leave the car at the Visitors’ car park and take to the bikes.

Cycle back to the T junction and turn right onto the D73 going downhill all the way past the Ulster Tower on your right. You will go over a small bridge over the river Ancre where British troops used to get their water. At the railway level crossing after the bridge, turn right onto the D50. After 200 yards, stop at the Ancre Cemetery on your left.

In November 1916 the last battle of the Somme was launched from the valley which is where you are standing. The majority of attackers were from the Royal Naval Division. In appalling wintry conditions, where mud was knee high the RND attacked the German defenders of Beaucourt. Each battalion of the RND was reduced by 200 men, due to sickness and sheer fatigue. The Hawke battalion of the RND suffered over 400 killed and wounded from a machine gun post concealed on the crest of the hill. The Hood battalion led by Colonel Freyberg were in action for twenty-four hours, and with the remnants of other depleted battalions captured Beaucourt. If ever a battle was won by the courage and leadership of one man it was this. Colonel Freyberg was wounded 4 times during the attack. His last wound exposed the vertebrae in his neck from a shell splinter.

Leave the cemetery, and within 100 metres on your left, you will find a track leading up the slope of the attack. After about 500 metres you should find the concrete remains of a German machine gun post. You should now be able to see a fine view of the ground the RND attacked over to reach Beaucourt. Retrace your footsteps and rejoin the road , turning left to cycle towards Beaucourt. In the bank on your left were several German dugouts that had to be bombed by the attacking British. After about a mile you will reach the scruffy remains of Beaucourt station on your right. This was the first objective of the RND. Here, Freyberg assembled various troops for a further attack on Beaucourt. Continue cycling towards Beaucourt up the hill. On your left you will find the RND memorial. It is worth a closer look, as it shows all the badges of the RND battalions who took part in this remarkable feat of arms.

Cycle back down the road, and turn right along the D163 (before you get to Beaucourt station) to BEAUMONT HAMEL. If you look left soon after turning onto this road you will see the slopes where the RND attackers descended, if you look immediately right, you will see the steep banks they had to climb in order to get to Beaucourt. Before you reach Beaumont Hamel, on your right you will see a long quarry face near the road. This was a 500 metre German dugout which gave the defenders of Beaumont Hamel shelter during the week-long bombardment that preceded the Somme attack.

Cycle through Beaumont Hamel, and then look out for a Scottish Cross Memorial on your right. Park your bikes at the base of the memorial. The memorial is at the bottom of the sunken lane used by the Lancashire Fusiliers to attack the German fortress of Beaumont Hamel. Few of these attacking troops even reached the German front line. With your backs to the Scottish memorial, look across the road towards Beaumont Hamel, at the hill to your right. It is covered in trees and shrubs. This marks the site of the famous Hawthorn Ridge. This was blown up by tunnellers at 7.20 am on the first day of the battle of the Somme. The Middlesex Regiment (consisting almost entirely of Public schoolboys) attacked the crater caused by the explosion. Most of them were killed and wounded and never reached the crater. If you retrace your footsteps towards Beaumont Hamel, after about 200 metres on your right, you will find steps and a track up to the Hawthorn mine crater. Descend into the crater through a gap in the “hedge”. It is a tribute to the miners who had to work in cramped conditions, in complete silence, moving forward 75 feet below the ground. They lived in constant fear of “counter mining” and being entombed alive.

Make your way back to the car park, and cycle downhill to the HAMEL crossroads. Turn left and you will soon find yourselves at the railway crossing which you must go over, retracing your footsteps up the steep hill to the Ulster Tower at the top of the hill. (More refreshments and a video slide show are available).

Standing with your backs to the gate of the Tower, look left and you will see the Connaught cemetery. Behind this is Thiepval Wood, where the Northern Irish sheltered before their attack. (The wood is full of trenches that have recently been excavated; however, they are only visible if you get a guided tour from Teddy, the northern Irishman who runs the Ulster Tower). The Irish were successful in their attack, storming up the hill behind you and to your left. However, they had to withdraw that evening, because their fellow attackers to their left and right were unable to support them in their ferocious charge. It is worth noting that somewhere in Thiepval Wood lie the remains of Billy McFadzean. Billy threw himself on a live hand grenade as the attacking Irish were making their way into the attack, thus preventing his comrades being affected by the blast. He was awarded the VC for his heroism.

To your right, at the end of the wall that encircles the Ulster Tower, is a track that runs almost parallel to the road you have just cycled up. About 150 metres down this track are the remains of a German machine gun post. It is worth sitting in this position to get an idea of the devastation it must have caused the attacking Irish as they emerged from the wood in front of you. In addition, you get a fine view of all the British positions in the Ancre Valley (including the RND Cemetery). Cycle past the Connaught cemetery on your right and up towards the Thiepval crossroads. Turn right and with any luck you should be back at the visitors centre!

(Full credit to Edward Hudson for this article which he specially produced for us).

Thiepval Memorial On the Portland Stone piers are engraved the names of over 72,000 men who were lost in the Somme battles between July 1916 and March 1918, most of whom died in the first Battle of the Somme between 1st July and 18th November 1916. Consequently, when the remains of a soldier listed on the memorial are found and identified, he is given a funeral with full military honours and his remains buried in the closest cemetery to his location his name is then removed from the memorial. This has resulted in numerous gaps in the lists of names

Poperinge/Talbot House/Tyne Cot - Route two

This tour is a short 30km and is very flat riding. The main reason to do this route would be to visit Talbot House in Poperinge and Tyne Cot cemetery. During the First World Wars Poperinge was situated a few kilometres behind the turmoil of battle on the Ypres Salient.

The British Army commandeered the quiet little town to accommodate the throbbing heartbeat of its war machine. Very quickly, Poperinge became a 24 hour-a-day metropolis; in 1917 approximately 250,000 men were billeted in the area... On the 11th December, 1915, in the centre of this lively metropolis, Chaplain Philip Clayton opened a soldiers’ house’. The large home of the Coevoet family was transformed into Every Man’s Club, where all soldiers were welcome, regardless of rank, On the suggestion of Colonel Reginald May, and despite the protest of the senior army chaplain Neville Talbot, the House was named ‘Talbot House’.

The name commemorates Gilbert Talbot, Neville’s younger brother, who was killed in action on the 30th July, 1915. Gilbert became the symbol of the sacrifice of a ‘golden generation of young men. For three years, the ‘Tommy’ found in Talbot House an alternative for the ‘debauched’ recreational life of the town. The initials of Talbot House became Toc H in the WWT phonetic alphabet. For hundreds of thousands, this site became a home from home’, where they found a little bit of humanity, rest and peace.

Messines Ridge - Route Three

It goes via Hill 60,HiII 62, Tyne Cot Cemetery, Passendale, Canadian Memorial (Brooding Soldier) then the German Cemetery at Landgemark. From here went on a cycle track (disused railway) to the canal then towpath to Ypres. Approx 40 km.

Messines Mesen-Wijschate ridge commands panoramic views over the surrounding flat countryside and was therefore a key military objective during the war. In 1914 the British gallantly but unsuccessfully defended the area against the Germans, who were sweeping towards the channel. The Germans soon fortified the ridge and high ground to Passendale. A major offensive commenced on 7 June 1917. Along an 8 kilometre arch of the Mesen Ridge, nineteen huge mines were detonated beneath the German lines - the explosions were so loud that they could be heard in London. The Germans were overwhelmed in their trenches as the New Zealanders, Australians and British advanced up the rise from the West. But the Germans counter-attacked and for the next two days, in a desperate but futile attempt to recapture the ridge, poured thousands of artillery shells on the allies. When the battle ended on 10 June, the southern end of leper (Ypres) salient was firmly in allied hands. The battle of Mesen was a great victory, particularly for the New Zealanders, who were assigned to capture the most heavily defended section of the ridge, including Mesen.

The allied forces then moved on to the dreadful battle of Passchendaele (Third leper), which commenced on 31 July 1917. In April 1918 the Germans launched their last offensive, reversing all the gains the allies had made in the previous year and recapturing the Mesen Ridge and beyond, to the village of Kemmel, Their victory was short-lived, for within months the allies, led by the King of Belgium, drove the Germans for the leper Salient. Mesen has been rebuilt, but will always remember those terrible years, and the men who gave their lives in Belgium’s defence.

Sanctuary Wood (Hill 62) Some of the heaviest fighting in the First World War was fought in the Battlefields of Sanctuary Wood between 19 15-16. The more frequently used name of this site is Hill 62. (Ridges were called Hills in the First World War, the number denotes how high above sea level they were). In October 1914 the area was silent and peaceful hence the use of the name Sanctuary Wood, but that began to change as by 1915 the woods became part of the Front-lines, The Germans launched many attacks in the area but was eventually stopped when the Canadians retook control of Sanctuary Wood. The trees were blasted and full of bullet holes and shell fragments. The first attack by the Germans in the war was also where Captain Noel Chavasse (the son of the Bishop of Liverpool) won his military cross in June 1915 for untiring efforts in personally searching the ground between our line and enemies for which many of the wounded owe their lives. Noel Chavasse took part in the attack on Sanctuary wood in September 1915.

Hill 60 was a low rise on the southern flank of the Ypres Salient and was named for the 60 metre contour which marked its bounds. Hill 60 was not a natural highpoint, but was created as a result of the digging of the nearby railway cutting, As such it was a strategically significant area of high ground. The hill had been captured by the Germans on December 10, 1914 from the French army. After the Race for the Sea, it was obvious the Hill had to be retaken. A great deal of fighting around Hill 60 was underground. In the first operation of its kind by the British, the Corps of Royal Engineers specialist tunnelling companies laid six mines by April 10, 1915. These mines (together with other unfinished mines) were filled with around 10,000 pounds (4,500 kg) of explosives, with the resulting explosions ripping the heart out of the hill over a period of some 10 seconds. It flung debris almost 300 feet (91 m) into the air and scattered it for a further 300 yards (270 m) in all directions.

1940 Hill 60 was also the site of a desperate battle between the Germans and part of ‘A” company of the 2nd Battalion Royal Scots Fusiliers on 27 May 1940, during the Second World War. Though the hill was the scene of a tremendous mortar and artillery barrage (Coy HQ being set up in and around the famous Anglo/German/Belgian pill-box) there was hand to hand action on the nearby Zwarteleen crossroads when a 2/RSF fighting patrol set off to destroy the German MG and mortar positions that had been set up there. The actions of this patrol enabled the evacuation of the defences on the railway and allowed for a successful withdrawal to the canal line and a general withdrawal towards St,Eloi, Kemmel and Dikkebus.

Other companies of 2/RSF held the railway line between hill 60 and the “Entrepot” at the canal bridge. To their right the Inniskillings and to their rear on the main road was D company in reserve. The 6/Seaforths held “the Dump”, where Sgt. Stewart was to win the DCM for his actions after taking over command when all the officers had become casualties. Though a defeat for the BEF, this and associated actions (including those to the west) kept the “Dunkirk corridor” open for about 24 hours longer, enabling the escape to the coast of thousands of retreating troops who would otherwise have “gone into the bag”. The memorial plate to the Australian miners involved in the First World War possibly bears the scars of this battle.

Above is the memorial, also known as “The Brooding Soldier”, commemorates the Canadian 1st Division in action on 22 to 24 April 1915. The Canadian division held its position on the left flank of the British Army after the German Army launched the first ever large-scale gas attack against two French divisions on the left of the Canadians. From the start of the battle at 17.00 hours on 22 April and for the next few days the Canadians were involved in heavy fighting.

In the period when the Canadian Division was in the line from 15 April to 3 May the division suffered heavy casualties of almost 6,000 killed, wounded or missing.

“During the 1st Canadian Division's period in the line (15 April-3 May), Canadian casualties (not including those of the P.P.C.L.I. [Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry]) numbered 208 officers and 5828 other ranks, infantry losses being almost equally distributed between the three brigades.”

The German cemetery at Langemark

The bronze statue of the four figures in this cemetery was created by the Munich sculptor Professor Emil Krieger.

His inspiration was a photograph of soldiers from the Reserve-Infantry-Regiment 238. The photograph was taken in 1918 as the soldiers mourned at the grave of a comrade. This became a well-known photograph which appeared in the German press during 1918.

The second soldier from the right was killed two days after the photograph was taken.

These figures are a particular feature of this cemetery. Slightly larger than life they immediately capture the eye as visitors enter the cemetery through the gatehouse building. The figures stand solemnly watching over so many thousands of German casualties of war. Even after visiting the cemetery numerous times, visitors will still find themselves drawn to look at the figures as they enter through the gate.

Ride to Brugge

A day in Brugge was also well worth it. We took the car with the bikes and parked at a village about 10 miles from Brugge. The canal cycle path straight into the center was by far the best way to do this.

Ancre Cemetry

Thiepval

Messines Ridge mine.

Hill 62

Tyne Cot

Sometimes WW1 places get mixed up with WW2.

Candanian Monument - Somme

Ance Cemetry

In awe of it all...

German cemetry

Image which inspired the German Statues

Canada Memorial

Brugge

Brugge